Entrepreneurship plays many important roles in a dynamic economy, perhaps none more important than innovation, where new products and services are introduced to customers. Ideally, innovative entrepreneurship can improve peoples’ quality of life, but it can also serve other important functions such as testing if customers are willing to pay for a new product or service (price discovery) or to “disrupt” an inefficient business model.

Because it is so essential, GEM teams measure innovative entrepreneurship every year. It is calculated by asking early-stage entrepreneurs (those actively planning a new venture or within their first 42 months of entrepreneurial operation) if their product or service is new to at least some customers AND that few or no businesses offer the same product or service. This demonstrates what percentage of an economy’s active entrepreneurs are introducing products or services that could potentially improve lives or at least make the economy a bit more dynamic.

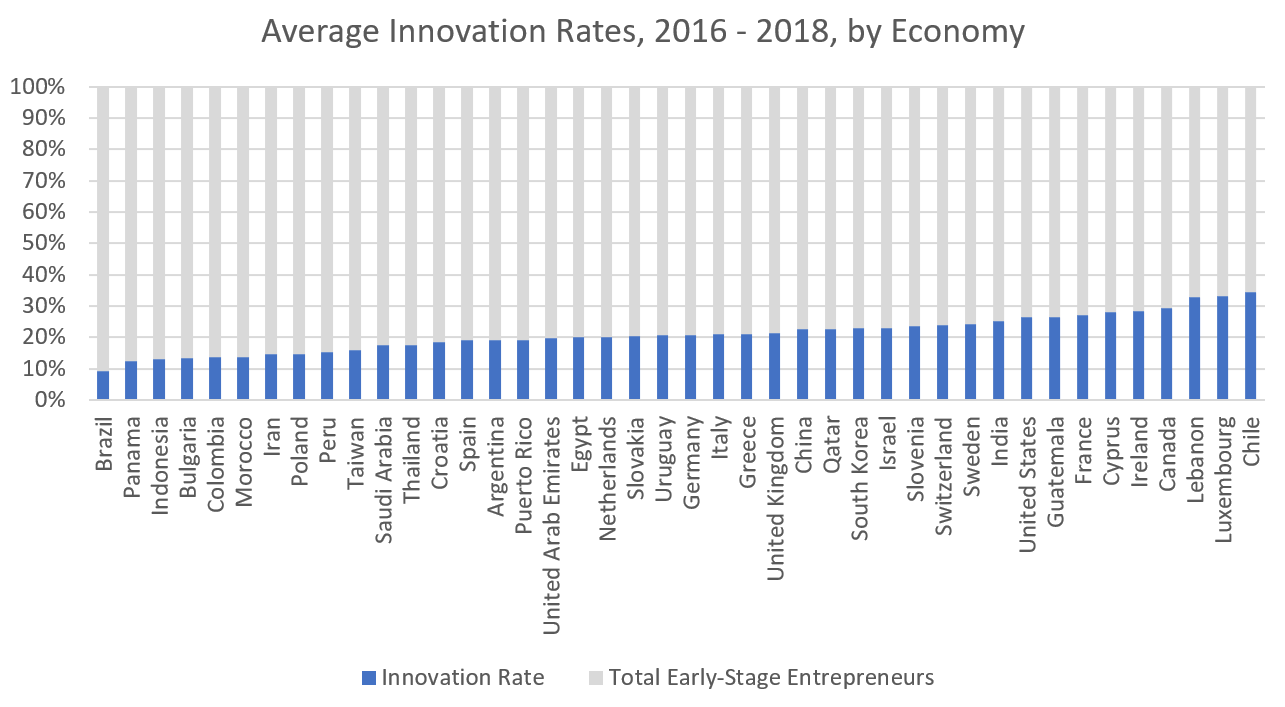

Below is a chart of the 42 economies that participated in all 3 of the last GEM survey cycles, graphed by their average innovation rates over that time:

What makes innovation interesting from an entrepreneurial research perspective is that it is highly subjective and contextual. Meaning, the technological absorption or customer sophistication of each individual economy will determine if a product or service is considered innovative. For example, in one instance food delivery may be considered innovative because it takes place over a recently-developed mobile app, but in a different economy this type of activity might not be considered an innovative service either because the mobile technology has not been developed or customers are not willing to use new services.

Because it is so context-specific, innovation rates are not determined by a country’s development status. This can be seen in the chart above where both developed and less-developed countries are mixed among the highest innovation rates. Some highly-developed countries appear in the middle and lower innovation rates.

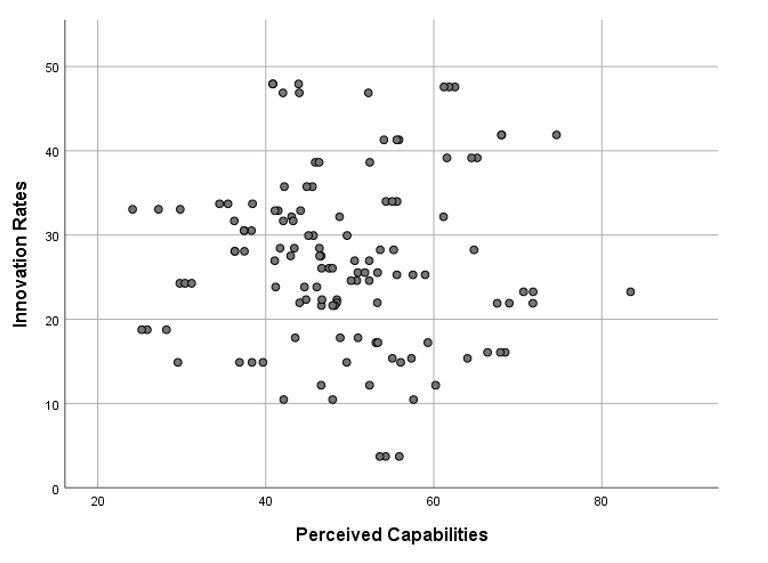

Other factors that might determine innovation, such as an entrepreneur’s perceived capabilities or opportunities, do not seem to have a strong relationship either. Below are charts showing the relationship between capabilities and opportunities, respectively, to innovation rates for all 42 economies from 2016-2018.

Capabilities:

Opportunities:

The lack of correlation between suggests again that innovation is not easily predicted by factors typically assumed to be essential to innovation. There may be other variables to consider, such as customer sophistication, i.e: a large enough group of consumers with the knowledge, technology and enthusiasm to try new products or services and the corresponding ability to enter those markets by early-stage entrepreneurs. More research could help improve our understanding.

Analysis by Forrest Wright (GEM Global Data Team)